Acrocanthosaurus atokensis was the supersized carnivore in North America during the Aptian-Albian ages. It took Acrocanthosaurus thirty some-odd years to grow into an adult dinosaur, but once it reached its full size it measured up to heavyweights like T. rex and Giganotosaurus—some of the biggest theropods to ever walk the earth.

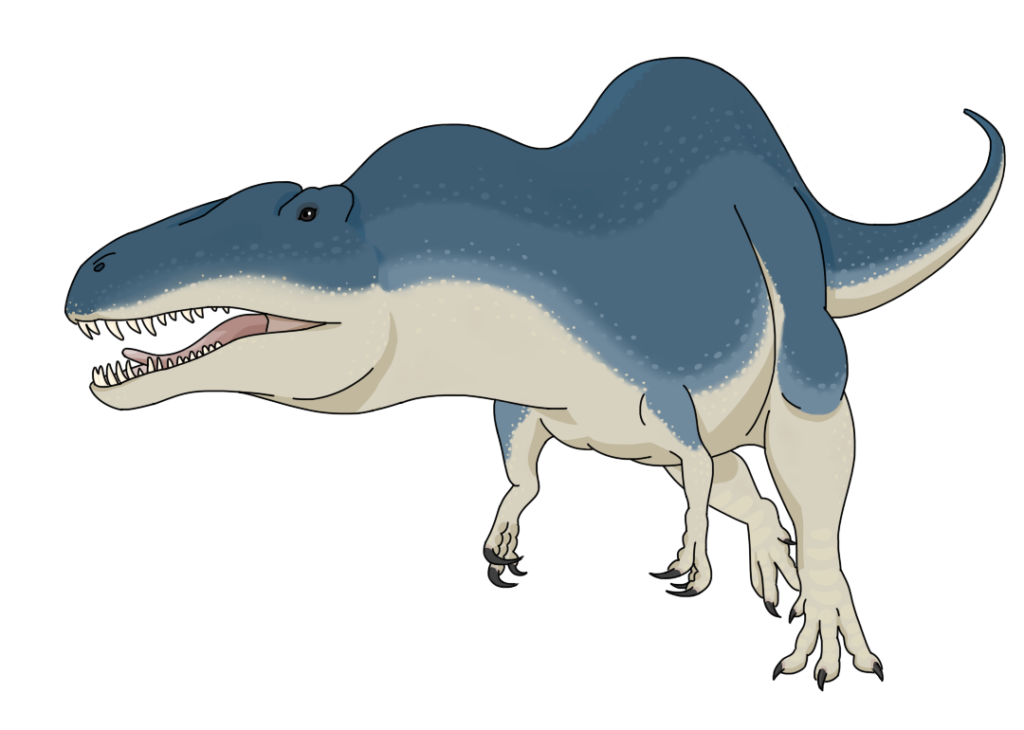

Scientists estimate an average Acrocanthosaurus to have been about as long as a school bus and tall enough to peek over the roof of a one-story house. It likely weighed somewhere between 8,000 and 12,000 pounds, in the same range as an African elephant.

This dinosaur’s most defining characteristic, besides a mouth full of serrated teeth, was the high ridge of neural spines running down its neck and back. Instead of a sail, scientists believe that these extra-tall backbones supported a muscular hump similar to a bison’s, which only added heft to its humungous frame.

A predator that size needed a lot of calories, and Acrocanthosaurus came with powerful jaws to do the job. One study estimated that it could crush an object in its back teeth with 16,894 newtons of force, a bite strength similar to an alligator’s. As Acrocanthosaurus grew, it worked up to bigger and bigger prey. Getting so large allowed Acrocanthosaurus to hunt dinosaurs like Tenontosaurus without taking much damage. It also gave them a fair shot at long-necked titanosaurs like Sauroposeidon, which, at nearly fifty tons, posed high risk and high reward.

But gigantism came with a price. With such heavy bodies, it’s doubtful that colossal theropods like Acrocanthosaurus could run. Instead, they had to resort to ambush hunting, pursuing prey more their speed, or scavenging a freebie here and there.

Being ridiculously huge also meant being ridiculously warm, leaving Acrocanthosaurus at risk of overheating. In order to survive, it needed some way to cool itself down. But could dinosaurs like Acrocanthosaurus control their own temperature like birds and mammals? Or were they at the mercy of outside temperatures like reptiles?

After studying how heat changes the molecular structure of animal bones, scientists compared Acrocanthosaurus fossils to ostrich, elephant, and alligator skeletons. As it turns out, Acrocanthosaurus bones more closely match ostrich and elephant bones, meaning they could hold a steady, stable temperature all on their own. This molecular study suggested that Acrocanthosaurus’ iconic hump helped it drop a few degrees. Meanwhile, the extra warmth generated by its brain could escape through the roof of its mouth, cooled by the air it breathed.

In Dinosaur Valley State Park, the Paluxy River uncovered a trail of large, three-toed theropod footprints possibly belonging to Acrocanthosaurus. These tracks show details down to the toepads and clawmarks, with tunnels where the dinosaur’s toes shoveled into the mud of the Western Interior Seaway’s ancient shoreline. The footprints run parallel to, and at one point even cross, a line of manhole-sized sauropod tracks.

Generations of paleontologists have studied these trace fossils to learn about how these dinosaurs moved and interacted. One popular reading of the prints is that Acrocanthosaurus may have been hunting the sauropod, and at one point even caused it to stumble. It’s difficult to know for sure if these particular dinosaurs ever met face-to-face, but one thing is certain. These rival giants were locked in an arms race that drove them to new heights—literally.

Acrocanthosaurus’ debut paper:

A paper on Acrocanthosaurus’ distribution, size, and growthrate:

Michael D. D’Emic, Keegan M. Melstrom, Drew R. Eddy,

Paleobiology and geographic range of the large-bodied Cretaceous theropod dinosaur Acrocanthosaurus atokensis,

Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology,

Volumes 333–334,

2012,

Pages 13-23,

ISSN 0031-0182,

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2012.03.003.

A paper on Acrocanthosaurus’ thermoregulation:

A paper on spines vs. humps:

Theropod biteforce estimates, including Acrocanthosaurus:

Sakamoto M. 2022. Estimating bite force in extinct dinosaurs using phylogenetically predicted physiological cross-sectional areas of jaw adductor muscles. PeerJ 10:e13731 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.13731

meet acrocanthosaurus

Acrocanthosaurus atokensis appears in chapter 26 of Cecelia and the Living Fossils.

Teenage necromancer + dinosaur bones. What could go wrong? See for yourself.