Deinonychus antirrhopus was a velociraptorine dinosaur that, during the early Cretaceous, prowled the two continents that now make up North America.

When the first Deinonychus fossils were discovered in 1969, paleontologist John Ostrum immediately recognized that the flexible wrist bones, long legs, scythe claws, and stiff tail suggested “an animal of great agility and speed and a highly predaceous mode of life.” These findings led his protégé, Robert Bakker, to the game-changing idea that dinosaurs may have been more active than expected, and in some cases even warm-blooded.

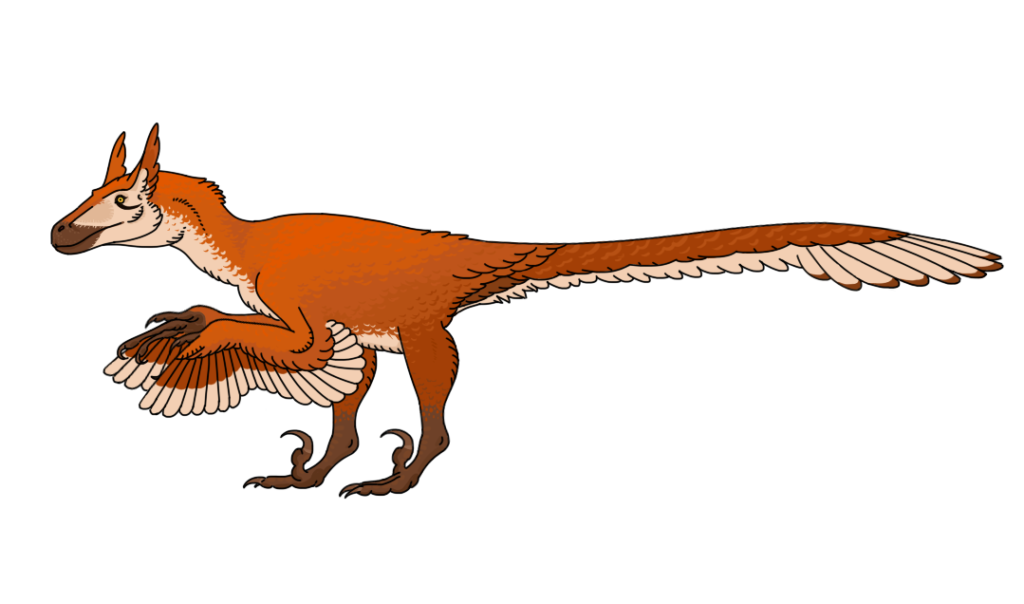

Even after the idea of sluggish, lizardlike dinosaurs was brought into question, raptors were still thought to be covered in scales. But as full-body fossils of German Archaeopteryx and Chinese Microraptor came to light, they revealed perfect portraits of non-avian dinosaurs with feathery coats, full wings, and fan-tipped tails. Even without these detailed fossil impressions, raptors’ bones leave us clues. For example, modern birds’ wing feathers are anchored in small holes in the arm bone. And these holes, called quill knobs, also exist on the arm bones of Velociraptor. Based on evidence from these dinosaurs, we can now confidently assume that Deinonychus was fully feathered.

Given the presence of feathers, some scientists have wondered if very young Deinonychus, with smaller, lighter bodies and proportionately longer wings, may have been strong tree-climbers with the ability to fly. Though this idea is fun to imagine and not impossible, it is tough to prove. And at 150 to 200 pounds full-grown, adult Deinonychus had zero chance of getting off the ground. So, if not for flying, what are feathers and wings good for?

The best way to answer this question is to ask a modern bird. Feathers allow animals to control their body temperature, provide camouflage for hiding or hunting, and allow them to send signals to communicate with others. But besides flight, there is one job that a pair of strong wings could do for a predator—locking down prey. When modern hawks catch a target in their talons, they sometimes flap their wings to balance on top of their prey and push them down against the ground. This technique, called raptor prey restraint or RPR, allows a bird to hold down their catch while they finish the kill or tear away chunks of meat. With two sickle-shaped killing claws and a bone-crunching biteforce similar to a spotted hyena, having wings for RPR would make Deinonychus a very successful predator.

This raises another popular question. How did raptors like Deinonychus hunt?

Deinonychus remains are often found nearby Tenontosaurus fossils, some of which bear damage from apparent raptor attacks. But this evidence left scientists wondering how a three-foot-tall raptor could possibly take on an animal roughly the size of a horse.

Considering that dinosaurs may have been more lively and intelligent than once believed, a clear solution to the weight class problem was pack hunting. After all, modern wolves can bring down a thousand-pound bull moose with the power of teamwork. However, after reevaluating Deinonychus through the lens of modern birds and reptiles, it has become more believable that this raptor actually hunted solo.

In 2007, Brian Roach and Daniel Brinkman pointed out that, unlike mammals, is extremely rare for birds or reptiles to hunt in coordinated packs. The closest behavior to this among alligators, Komodo dragons, and sometimes even vultures is mobbing, where one gutsy bite from a hungry predator triggers a feeding frenzy. In this way, a large animal can be downed and eaten by a group of carnivores who would normally never cooperate or share. If Deinonychus did hunt alongside other Deinonychus, it probably looked less like a pack of wolves and more like a horde of zombies.

The more we learn about how birds of prey and carnivorous reptiles hunt, the more likely it seems that a lone Deinonychus may have been able to bring down a bigger target. Golden eagles, for instance, are known to bring down animals up to ten times their size. That math brings Deinonychus’ odds of taking down a half-ton, subadult Tenontosaurus more into the realm of possibility. This information, on top of the fact that Deinonychus seemed to regularly squabble with and even cannibalize other Deinonychus, led Roach and Brinkman to the conclusion that our favorite raptor was happiest alone.

But don’t be too sad for antisocial Deinonychus. As it turns out, the raptor was probably a pretty good parent. Deinonychus bones have been found over fossilized eggshells, and paleontologists believe that the raptor was likely watching over its nest. When these eggs were sampled on a microscopic level, it became clear that the shells were originally blue with brown speckles, probably to blend into the forest floor. So, though they went on to live solitary and brutal lives, each Deinonychus started out safe and cozy under its parents’ feathers.

Deinonychus’ debut paper:

Ostrom, John H. “A new theropod dinosaur from the lower Cretaceous of Montana.”

A paper on Velociraptor quill knobs:

Turner, A.H., Makovicky, P. J., and Norell, M.A. 2007. Feather quill knobs in the dinosaur Velociraptor. Science, 317, No. 5845:1721–1723.

A paper speculating arboreal and possibly flighted juveniles:

Parsons WL, Parsons KM (2015) Morphological Variations within the Ontogeny of Deinonychus antirrhopus (Theropoda, Dromaeosauridae). PLoS ONE 10(4): e0121476. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0121476

A paper on raptor prey restraint:

Fowler DW, Freedman EA, Scannella JB (2009) Predatory Functional Morphology in Raptors: Interdigital Variation in Talon Size Is Related to Prey Restraint and Immobilisation Technique. PLoS ONE 4(11): e7999. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0007999

A paper on Deinonychus’ bite force:

Paul M. Gignac, Peter J. Makovicky, Gregory M. Erickson & Robert P. Walsh (2010) A description of Deinonychus antirrhopus bite marks and estimates of bite force using tooth indentation simulations, Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 30:4, 1169-1177, DOI: 10.1080/02724634.2010.483535

A paper on Deinonychus’ hunting behavior:

Brian T. Roach and Daniel L. Brinkman “A Reevaluation of Cooperative Pack Hunting and Gregariousness in Deinonychus antirrhopus and Other Nonavian Theropod Dinosaurs,” Bulletin of the Peabody Museum of Natural History 48(1), 103-138, (1 April 2007). https://doi.org/10.3374/0079-032X(2007)48[103:AROCPH]2.0.CO;2

The Deinonychus egg paper:

Gerald Grellet-Tinner, Peter Makovicky; A possible egg of the dromaeosaur Deinonychus antirrhopus: phylogenetic and biological implications. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 2006;; 43 (6): 705–719. doi: https://doi.org/10.1139/e06-033

The egg color paper:

Wiemann, J., Yang, TR. & Norell, M.A. Dinosaur egg colour had a single evolutionary origin. Nature 563, 555–558 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0646-5

meet deinonychus

Deinonychus antirrhopus appears in chapter 21 of Cecelia and the Living Fossils.

Teenage necromancer + dinosaur bones. What could go wrong? See for yourself.

Horde of zombies made me shudder. Raptors are scary enough. Fabulous imagery and a really great synopsis. Thanks for bringing this ancient creature to life on the page. And for making me more grateful than ever that it is ancient.