Sauroposeidon proteles was one of the last giant sauropods to inhabit North America. In the year 2000, it was named as a new species based on four unusually long neckbones found in Oklahoma. Little did paleontologists know that they’d met this dinosaur before!

Back in the 1980’s, a trove of sauropod fossils was discovered at Jones’ Ranch in Glen Rose. Besides plenty of bones from at least four individual sauropods, scientists also found rare skull material—something less than a third of all sauropod genera have evidence for, since these dinosaurs’ heads are so fragile compared to the rest of their bodies. The new dinosaur was named Paluxysaurus jonesi, after the Paluxy River and Bill Jones, who owned the ranch where the fossils were found.

Later, when scientists compared Sauroposeidon and Paluxysaurus, they found that the bones these dinosaurs had in common looked identical, except that Paluxysaurus’ were about two-thirds the size. Interestingly, Paluxysaurus’ bones also showed signs of unfinished growth. This led paleontologists to believe that these were not two separate species, but instead an adult specimen and a juvenile specimen of the same animal.

In 2012, scientists officially relabeled Paluxysaurus as a younger version of Sauroposeidon. Their shared fossils not only showed how large a so-called Paluxysaurus could get once it reached adulthood, but revealed a much more complete picture of Sauroposeidon.

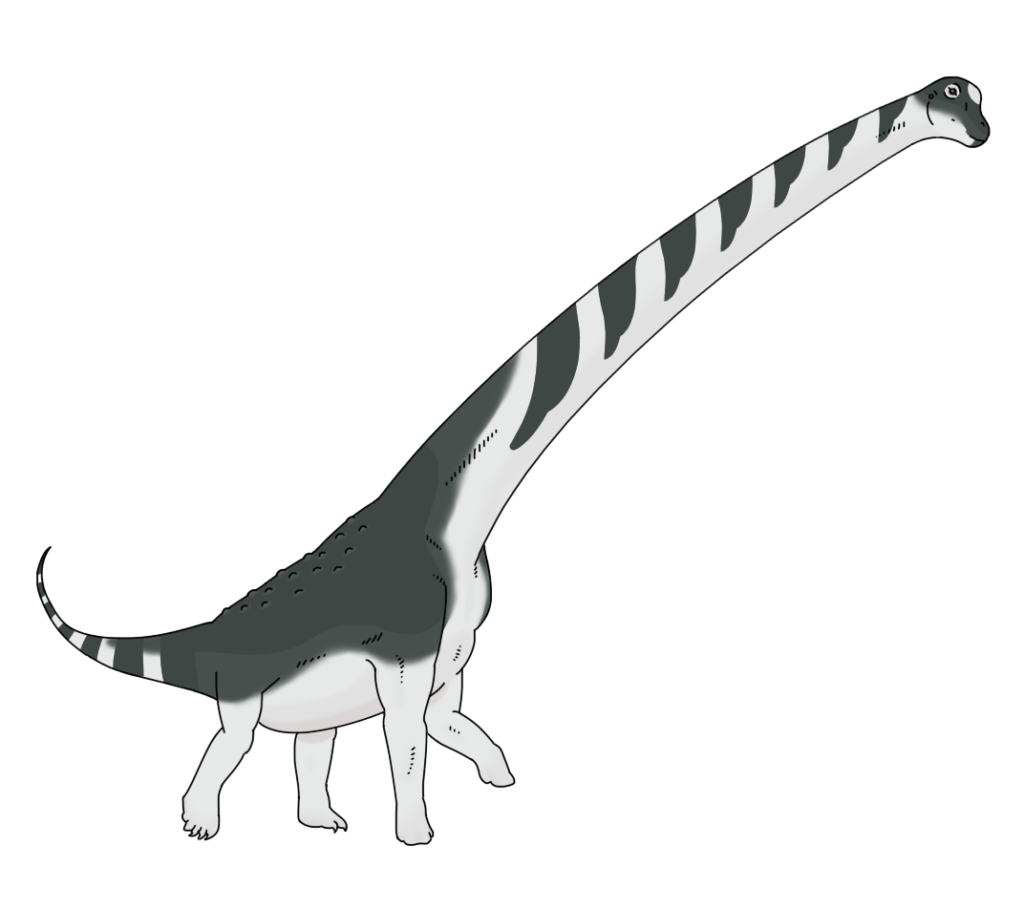

The resulting dinosaur had high, giraffelike shoulders and an unusually long neck—even for a sauropod. Pound-for-pound, Sauroposeidon may not have been the biggest dinosaur on earth, but these features may have made it one of the tallest. An outdated model comparing it to brachiosaurids estimated that it could hold its head almost sixty feet in the air. However, since Sauroposeidon was reclassified as a titanosaur, this model has yet to be officially reexamined. Still, to browse from 75-foot-tall evergreen trees and discourage huge predators like Acrocanthosaurus, Sauroposeidon would need every extra inch it could get.

Though Sauroposeidon now has more fossil evidence than it started with, some parts of its skeleton are still a mystery. Luckily, paleontologists are able to work out what these unknown parts probably looked like based on other clues.

For example, even though we have no skin impressions or preserved tissue for Sauroposeidon, we do know that many titanosaurs had boney bumps on their skin called osteoderms, which fit into a mosaic of much smaller scales that covered their bodies. Sauroposeidon probably also had these studs on its back, which served as armor and possibly storage for important nutrients.

Another one of this dinosaur’s missing pieces is its toes. But by looking at the foot bones of other related sauropods, scientists can make an educated guess about their shape. Most titanosaurs’ front toes were bundled together like mittens, forming a padded ‘hoof’ that left behind a horseshoe-shaped print. Their hind feet were stumpy like an elephant’s, with large, curved claws that poked deep tunnels in the toes of tracks they left behind.

Tracks are a great way to learn the shape of dinosaurs’ feet, but they can also hint at how dinosaurs might have behaved. The Glen Rose formation is famous for its many dinosaur trackways, particularly the sauropod footprints in the bed of the Paluxy River. But these popular footprints aren’t the only prints in Texas that help us imagine how long-necked giants like Sauroposeidon may have moved.

About 200 miles away in Kendall County, another set of sauropod tracks was found in the Glen Rose formation—but it seems that the dinosaur who left these tracks behind was not simply walking. Along this trail, the back footprints disappear, leaving only prints from the two front feet.

Was this dinosaur walking on its hands? Possibly, though probably not like an acrobat. In this case, scientists believe that the dinosaur may have been punting, pulling itself along the muddy bottom with its front feet while its back legs and tail floated behind.

In almost forty years, our image of Sauroposeidon has completely transformed. As nature wears old rock away to reveal new layers of history, and as scientists examine fossils left behind by other Texan thunder lizards, it’s only a matter of time before we discover something new.

Sauroposeidon’s debut paper:

Mathew J. Wedel, Richard L. Cifelli & R. Kent Sanders (2000) Sauroposeidon proteles, a new sauropod from the early Cretaceous of Oklahoma, Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 20:1, 109-114, DOI: 10.1671/0272-4634(2000)020[0109:SPANSF]2.0.CO;2

Paluxysaurus’ debut paper:

Paluxysaurus is Sauroposeidon:

meet sauroposeidon

Sauroposeidon proteles appears in chapter 28 of Cecelia and the Living Fossils.

Teenage necromancer + dinosaur bones. What could go wrong? See for yourself.